In policy discussions over the past few years, a consensus has been reached. The country’s new growth model, which is based on boosting productivity and innovation, is essential in order to avoid the middle-income trap, become a high middle-income country, and achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

The key question of increasing productivity and competitiveness of enterprises in the country’s next stage of development was noted by Deputy Prime Minister Vuong Dinh Hue at the recent workshop on Vietnam’s economic growth for 2021-2030 with a vision towards 2045. The event, co-organised by the prime minister’s scientific advisory group, the Ho Chi Minh Political Academy, the Academy of Social Sciences (VASS), and the World Bank, delved into one of the most important questions that the Socio-Economic Development Strategy for 2021-2030 and the Socio-Economic Development Plan for 2021-2025 is seeking answers to.

The recently-released joint study report by the VASS, the Ministry of Planning and Investment, and the United Nations Development Programme is a contribution to the search for the answers to this important question.

While it is generally known that the country’s labour productivity is low compared to many countries in the region, the causes of this relatively low productivity are not well understood. By examining the productivity and competitiveness of Vietnam’s manufacturing enterprises at Vietnam Standard Industrial Classification two–digit sub-sector level, the report sheds light on the specific bottlenecks and opportunities for improving productivity and competitiveness in different manufacturing sub-sectors.

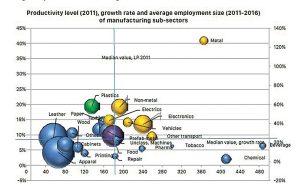

The report highlights that largest manufacturing subsectors in terms of employment output and export – garment, leather and footwear, and food processing – experienced low labour productivity growth; and sub-sectors with higher productivity in 2011 grew slower during 2011-2016 (figure 1), reiterating the reduced scope for structural change to achieve productivity improvements and implying efforts should focus on “within sub-sector” factors to improve manufacturing labour productivity in the future.

The report, for example, highlights that foreign direct investment (FDI) has a very high value-added share in electronics (98 percent), garments (59 percent), and leather and footwear (82 percent) – three of Vietnam’s largest manufacturing sub-sectors in terms of employment and exports. However, at the same time, the linkage of FDI to domestic businesses is still low. The strategy of foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) focussing on the final stages of assembling products in Vietnam, combined with the inability of domestic firms to move up to higher value chain stages (to become the essential, first or second-tier suppliers to FIEs), resulted in low labor productivity in many sub-sectors that FDI dominates.

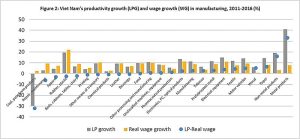

Wage growth that is higher than labour productivity growth in several sub-sectors, for example, leather, footwear, other vehicles and garment (figure 2) indicates the risk of foreign investors moving their assembling plants to other countries where the labour cost is lower. The report assesses that wage growth, combined with the risk of losing simple repetitive jobs to automation, poses a real challenge for Vietnam’s labour-intensive sub-sectors in continuing to create more jobs for Vietnamese workers.

The report also identifies important opportunities, for example, it highlights food processing as a promising sub-sector that is dominated by domestic private companies and based on the comparative advantage of Vietnam being among the world’s large producers of several agriculture commodities such as catfish, shrimp, coffee, tropical fruits, and others. The further development of domestic companies in the food processing sub-sector and improvement of their branding, marketing, and technology upgrading will enhance their productivity and competitiveness in both local and international markets. At the same time, it will also help these companies lead in developing and deepening local value chains, supporting the agriculture sub-sector in ensuring higher quality, food safety and capturing more value addition.

The report underscores the importance of three trends in Vietnam: (i) emerging domestic private companies with the potential to lead local value chain development such as cars, electric bikes, smartphones and food processing; (ii) some rather competitive domestic branded products in the local market such as washing detergent and fabricated metal products; and, (iii) rapidly increasing number of first and second-tier suppliers to FIEs though the overall number remains relatively small – especially in electronics and motor and other vehicles sub-sectors.

To help Vietnam’s manufacturing companies improve their productivity and competitiveness, concerted efforts with different line ministries will be required to develop and implement integrated actions across several areas. This includes actions that range from attracting higher quality FDI and SME development by creating win-win linkages between FIEs and domestic companies, to designing and implementing new industrial policies, research and development, and innovation policies, with the aim of “creating an ecosystem for generating winning companies”, rather than picking or rewarding the winners.

The report highlights the need for not only continuing to improve the business environment which will be beneficial to all enterprises but also providing supports that are much more tailored to help domestic companies overcome bottlenecks, specific to different subsectors and clusters of companies, in participating in local value chains, growing in size and moving up in value chains.

This is key to help build SME capacity in product design, technology upgrading, branding and marketing that are key in capturing more value addition and enhancing their competitiveness, first in local markets laying the foundation for their future ability to compete in international markets. This will also require government agencies to adopt an “experimentation approach” and new ways of working with private enterprises. For example, this could include convening platforms that bring together government and private sector (domestic and international) to identify specific productivity and competitiveness bottlenecks that enterprises face in specific subsectors, and design and implement tailored actions they can take.

Despite the challenges ahead, with the combination of Vietnam’s resilient and innovative entrepreneurs, and the strong commitment of the government to take actions in serving and nurturing businesses, Vietnam’s enterprises can play a key role in building their productivity and competitiveness, and contributing to Vietnam’s growth and aspirations for becoming a high middle-income country and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

[content_block id=4039 slug=posts-footer]