China and Russia are the world’s largest markets for residency and citizenship by investment, and they will likely remain so for quite some time. It’s natural, then, for investment migration companies to focus a lot of their efforts in these critical regions.

But because Russians and Chinese have been investing their way into residence permits and citizenships for decades already, those markets are mature and relatively saturated. As an example, China’s Guangdong province alone, it is said, has more than a thousand investment migration firms. There will never in human history be another China; that ship has sailed.

But there are other ships, with plenty of tickets left.

What if you’re an up-and-coming firm wanting to carve out a share of a new frontier market rather than take up competition with the behemoths in established markets? What’s the next colossal market, where it’s still early days and the going is still good? Let’s try finding a new land.

To be a big market for residency and citizenship by investment, a country needs the following four components:

– A large population

– Lack of liberty (limited political freedoms and property rights, lack of safety/stability etc)

– Considerable travel restrictions

– A high number of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs)

By the method of elimination, we should be able to come up with an answer. Below is a list of the world’s 20 most populous countries.

China – 1.40bn

India – 1.33bn

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 264m

Brazil – 209m

Pakistan – 197m

Nigeria – 191m

Bangladesh – 165m

Russia – 143m

Mexico – 129m

Japan – 127m

Ethiopia – 105m

Philippines – 104m

Egypt – 97m

Vietnam – 94m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 81m

Iran – 81m

Turkey – 80m

Thailand – 69m

Now, let’s deduct the countries that already have mature investment migration markets:

China – 1.40bn

India – 1.33bn

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 264m

Brazil – 209m

Pakistan – 197m

Nigeria – 191m

Bangladesh – 165m

Russia – 143m

Mexico – 129m

Japan – 127m

Ethiopia – 105m

Philippines – 104m

Egypt – 97m

Vietnam – 94m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 81m

Iran – 81m

Turkey – 80m

Thailand – 69m

Next, let’s cut the ones that don’t have considerable travel restrictions, i.e. countries that have visa-free travel to Schengen:

China – 1.40bn

India – 1.33bn

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 264m

Brazil – 209m

Pakistan – 197m

Nigeria – 191m

Bangladesh – 165m

Russia – 143m

Mexico – 129m

Japan – 127m

Ethiopia – 105m

Philippines – 104m

Egypt – 97m

Vietnam – 94m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 81m

Iran – 81m

Turkey – 80m

Thailand – 69m

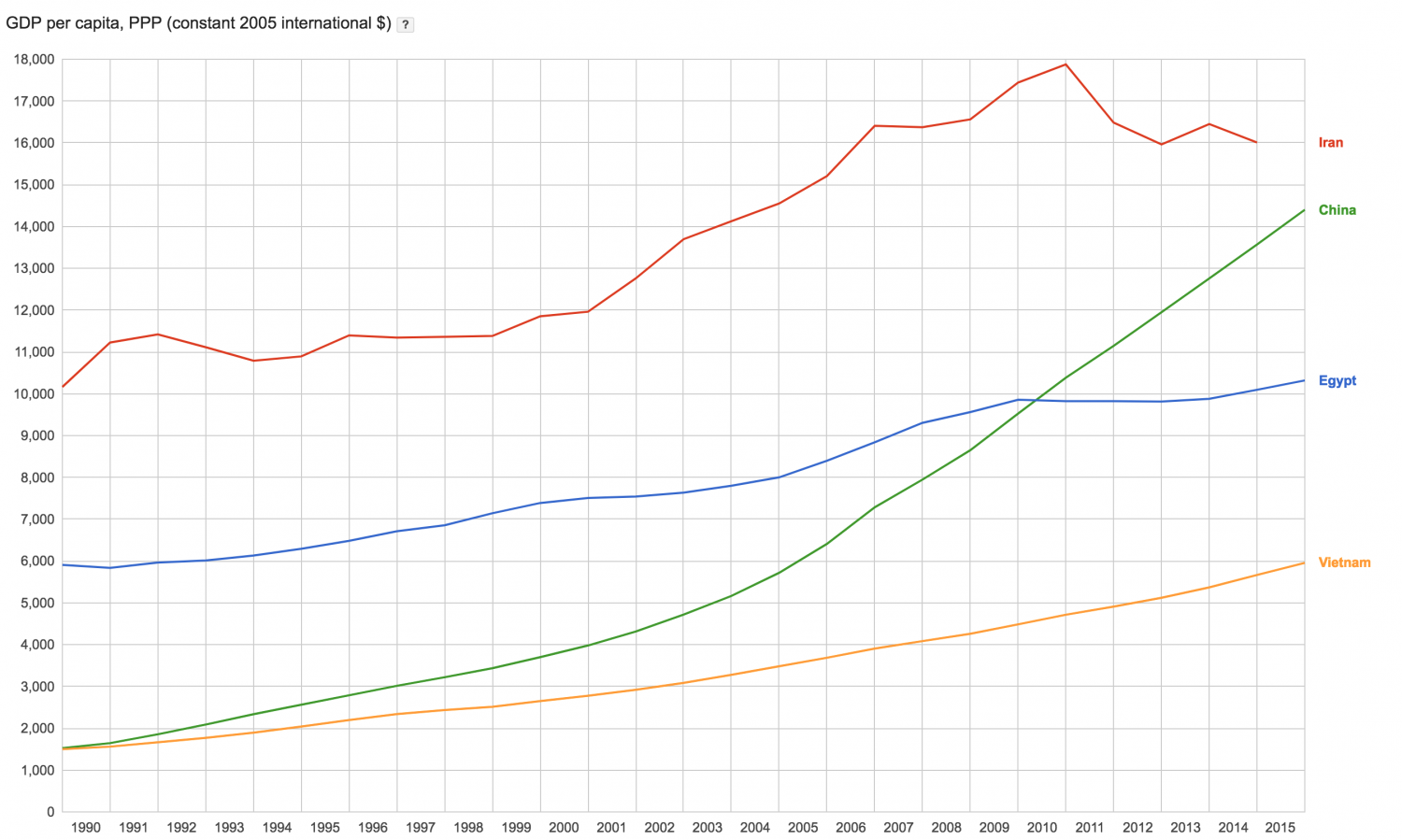

13 countries left. Let’s cut the countries that aren’t yet rich enough to have a high concentration of HNWIs (setting the bar at US$6,000 GDP per capita, in purchasing power terms):

China – 1.40bn

India – 1.33bn

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 264m

Brazil – 209m

Pakistan – 197m (GDP(PPP) per capita is US$4,900)

Nigeria – 191m

Bangladesh – 165m (GDP(PPP) per capita is US$3,581)

Russia – 143m

Mexico – 129m

Japan – 127m

Ethiopia – 105m (GDP(PPP) per capita is US$1,735)

Philippines – 104m

Egypt – 97m

Vietnam – 94m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 81m (GDP(PPP) per capita is US$803)

Iran – 81m

Turkey – 80m

Thailand – 69m

11 countries down, 9 to go. Among the chief motivating factors for investment migration clients is a concern for the safety of their assets due to a lack of respect for property rights, indoctrinating and propagandizing educational systems, as well as the lack of individual rights and personal liberty and so on. In a word; freedom. The less you have of it in a country, the more you want to leave.

We’ll use the Freedom in the World Index to determine which countries to cut from the list. The Freedom in the World Index classifies countries as free, partly free or not free, based on the level of civil liberties and political rights.

Let’s remove the countries classified as free and partly free, and keep the ones listed as not free:

China – 1.40bn

India – 1.33bn (free)

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 264m (free)

Brazil – 209m

Pakistan – 197m

Nigeria – 191m (partly free)

Bangladesh – 165m

Russia – 143m

Mexico – 129m

Japan – 127m

Ethiopia – 105m

Philippines – 104m (partly free)

Egypt – 97m

Vietnam – 94m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 81m

Iran – 81m

Turkey – 80m (partly free)

Thailand – 69m (partly free)

3 countries left, now we’re getting somewhere. Since we’re trying to figure out where the biggest investment migration markets will emerge in the future, let’s look at their projected population and GDP figures five years hence:

Country – Population 2022 – US$ GDP (PPP) per capita 2022:

Egypt – 100m – US$16,813

Vietnam – 100m – US$9,102

Iran – 88m – US$24,634

All three of these countries are excellent candidates for the next big investment migration market, but we want to find out which is the single best prospect, which means that this analysis will have to move from science to art, from rigid analysis to qualitative conjecture. Let’s take a closer look at all three:

Iran

Iran is not a poor country. Its GDP per capita, in PPP terms, is on par with countries like Argentina and Montenegro. But Iranians face extreme difficulties in terms of getting their money out. The country has tremendous pent-up demand for second passports and residence permits, but these products are far less accessible to Iranians than to other nationalities because of political sanctions and banking restrictions, as well as the listing of Iranian nationality as restricted in many popular investment migration destinations.

This is not to say that it is impossible for Iranians to obtain second citizenships or residence permits – there are ways around it, such as residing for a long enough time in a third country – merely that the obstacles placed in their way cause the stream of potential clients from Iran to be much lighter than it ordinarily would be.

Iran, while conditions could change suddenly with the lifting of sanctions, is not the prime candidate.

Egypt

Egypt has plenty of HNWIs who have no shortage of reasons for wanting to get out. Political turmoil, government repression and a non-negligible level of terrorist threats plague the country.

But the mother tongue of most Egyptians is Arabic, and virtually everyone in the country’s economic elite speaks English as well, which means they have easy access to information and services from companies based in Dubai, the Middle East’s investment migration hub. They can easily travel to the UAE or Istanbul for a consultation, or pick up the phone and speak directly to a client advisor in London or Montreal. I suppose firms could open offices in Cairo, but they could get virtually the same results with a network of introducers.

Egypt is a tremendous market, but by its connectedness to existing markets through culture, language and geography, it’s already covered and catered to.

That’s not the case with the final country on the list.

Vietnam

While many in the younger generations speak English, finding someone in the above-40 bracket with command of any language other than Tieng Viet is more the exception than the rule. While Arabic is a lingua franca and also a mother tongue throughout large swaths of the Middle East, only the Vietnamese speak Vietnamese.

Egyptians can travel to Dubai for a consultation in Arabic or English, but the Vietnamese won’t travel to Shanghai for the same. No, they need the information and consultants to come to them, in their own language.

It’s got nearly 100 million people, and its economy is among the fastest growing in the world, regularly posting GDP-expansions of 6-8% a year.

You can predict much of the trajectory of the Vietnamese investment migration market simply by looking at what’s taken place in China over the last few decades because these two countries have so much in common politically and economically:

– They are both former communist countries (still communist in the name) that have opened up gradually to become market-based.

– They are both experiencing decades-long trends of rapid economic growth as a result of economic liberalization.

– They have very limited mobility.

– They both have well-established diaspora networks in Western countries and a cultural propensity for emigration.

– They both have very limited political freedoms and property rights.

– China introduced their Reform and Opening Up policy in 1979, Vietnam the Doi Moi reforms in 1986.

Hence, Vietnam is such a potential market for immigration programs.

[content_block id=4039 slug=posts-footer]